Introduction:

Cheques and bank guarantees are two fundamental financial instruments in Qatar’s commercial practice, serving as tools to secure payments and obligations in contracts. Each instrument carries its own legal implications and is governed by specific laws and regulations. This bilingual article explores the legal role of cheques as payment and credit tools under Qatari law, the liabilities arising from bounced cheques (including criminal consequences), and the latest reforms up to 2024. It also delves into bank guarantees – their types, mechanics, and legal enforcement – in the context of Qatar’s commercial contracts. We will clarify the rules for on-demand guarantees, relevant Qatar Central Bank regulations, and international standards like the ICC’s URDG 758. By comparing cheques and guarantees as risk mitigation strategies, readers (especially businesses and investors in Qatar) will gain insight into which instrument suits their needs and how to use them properly. The content is tailored for clients seeking advice on contract enforcement and financial securities, emphasizing accuracy to Qatari law and a formal tone suitable for legal consultation.

Cheques and bank guarantees are vital in Qatar’s commerce – understanding their legal standing helps prevent payment disputes.

Cheques as Payment Instruments in Qatari Law

Legal Nature of Cheques:

In Qatar, a cheque (ʿcheck) is a negotiable instrument that functions as an order by the account holder (drawer) to their bank (drawee) to pay a specified sum to the beneficiary (payee). Under Qatari law – notably the Commercial Law No. 27 of 2006 (referred to as the Trade Law) – cheques are treated as a form of payment almost equivalent to cash. The law’s philosophy is that a cheque should circulate and be accepted confidently like money. As such, the law provides strong legal protection to cheques: primarily, by criminalizing the act of issuing a cheque without sufficient funds. It is common in Qatar (as in many GCC countries) to use post-dated cheques as a credit instrument – for example, a series of monthly post-dated cheques might be given by a tenant to a landlord, or by a purchaser to a supplier, to guarantee future payments. However, legally a cheque is always payable on demand (on the date written or if no date, upon presentment). The practice of post-dating does not change the fact that if a cheque is presented and bounces, legal consequences ensue.

Criminal Liability for Bounced Cheques:

Qatar historically has stringent penalties for dishonored cheques. Article 357 of the Penal Code (Law No. 11 of 2004) – as referenced in practice – makes it a criminal offense to issue a cheque that bounces for insufficient funds. Specifically, if a person draws a cheque in bad faith without enough balance or if they withdraw the funds after issuing the cheque or instruct the bank to stop payment unlawfully, they can face criminal charges. The punishment upon conviction can include imprisonment from 3 months up to 3 years, and a fine of at least QAR 3,000. Notably, Qatari law does not require the prosecution to prove an intent to defraud for the basic offense of a bounced cheque – issuing a cheque that bounces is per se a crime. However, evidence of fraudulent intent or serial offenses could affect sentencing. The Penal Code also provides a unique remedy: the court, upon finding the drawer guilty, must order them to pay the value of the cheque and any related expenses to the beneficiary. This means the criminal court’s judgment can include an order for restitution (the cheque amount) without the beneficiary having to file a separate civil lawsuit, which strengthens the position of the payee.

It’s important to note that paying the cheque amount after the complaint is filed but before final judgment can lead to cessation of criminal proceedings (often, prosecutors or judges will drop charges if the issuer settles the amount and the beneficiary withdraws the complaint, treating the matter as resolved). However, this is discretionary and not an absolute right; the law was amended to allow more flexibility in reconciliation of cheque cases. Also, under Article 604 of the Trade Law (27/2006), if a person is convicted of a cheque-related offense, the court may order measures such as withdrawing the cheque book from the convicted person and barring them from obtaining new cheque books for a certain period. This is aimed at preventing repeat offenders from misusing cheques.

Cheque Reforms in 2024:

Qatar undertook significant reforms in 2024 to modernize and expedite the handling of bounced cheques. Law No. 1 of 2024, which took effect in April 2024, amended provisions of the Commercial Law (Trade Law) to introduce new mechanisms for cheques. A key amendment was to Article 585 of the Commercial Law, introducing the concept of partial payment of cheques by banks. Under the new rule, if a cheque is presented and the account has insufficient funds to cover the full amount, the bank is now required to pay the holder whatever funds are available (a partial payment), unless the holder explicitly refuses. The bank must record this partial payment on the back of the cheque and give the cheque back to the holder along with a certificate of the amount paid. The holder can then use that certificate plus the original cheque (noting the partial payment) as evidence to claim the remaining unpaid balance. This reform effectively reduces the number of “completely” bounced cheques, by ensuring beneficiaries get at least a portion of their money immediately from the bank, and streamlines their ability to collect the remainder. The rationale is to minimize the legal burden and disputes from bounced cheques by at least providing partial recovery and clear documentation of the unpaid portion.

Another major change came with the issuance of Law No. 4 of 2024 (the Judicial Enforcement Law). Effective from November 2024, this law revolutionized enforcement procedures in Qatar. One of its most notable provisions is that cheques have been elevated to the status of “enforceable documents” (executory instruments). In practice, this means a cheque that has been dishonored can be taken directly to the new specialized Enforcement Court for execution, rather than requiring a separate civil judgment. The creditor (cheque holder) can file an enforcement request attaching the bounced cheque (and presumably the bank’s “insufficient funds” memo or the new partial payment certificate) and the Enforcement Judge has authority to treat it like a judgment debt. The judge can then swiftly order measures like asset seizure, freezing orders or travel bans against the debtor, to compel payment. This dramatically speeds up recovery on dishonored cheques, which previously could only be pursued via a criminal complaint or a civil lawsuit (which took time). Now, instead of waiting perhaps years for a civil judgment, the cheque itself (once bounced) is akin to a judgment. This change “boosts confidence in financial transactions” by assuring payees that they have a fast-track enforcement route for cheques. It also aligns with practices in some neighboring countries (e.g. UAE) that have recently given greater civil weight to cheques while reducing criminal emphasis.

Decriminalization of Minor Offenses:

In parallel with these enhancements, Qatar has taken steps to slightly soften the criminal regime for cheques, especially for minor cases. Recent updates (via policy or perhaps an internal directive in 2022–2023) indicate a shift towards imposing fines instead of jail for minor bounced cheque offenses. While the law still provides for imprisonment, authorities have discretion to treat minor instances (perhaps low-value cheques or first-time incidents) as contraventions penalized by fines to alleviate the burden on the penal system. The idea is to focus on financial restitution rather than incarceration when the offense is not egregious. However, this doesn’t mean bouncing a cheque is no longer serious – it remains illegal, but the response may be calibrated to the offense severity.

Additionally, mediation and settlement are now encouraged in cheque disputes. Prosecutors and courts may allow parties time to work out a payment plan or mediated agreement, and if the issuer makes good on the cheque, the case can be closed (with consent of the beneficiary). Qatar’s legal culture often informally facilitated such settlements; now it’s more formally promoted as part of the process to reduce court caseloads.

Digitalization:

Qatar has also introduced digital avenues for filing cheque complaints and tracking them. For instance, the Ministry of Interior’s Metrash2 app and e-services allow a beneficiary of a bounced cheque to file a police complaint online without physically visiting the police station. This e-complaint is then processed through the system. Such measures, while administrative, reinforce the policy of making enforcement and legal recourse more efficient and user-friendly.

In summary, a cheque in Qatar is a legally powerful instrument: it enables quick criminal action against a defaulting issuer and now also offers expedited civil enforcement. These potent remedies mean that issuing a cheque carries serious responsibility. It’s why many companies and individuals accept cheques confidently – because they know the law strongly incentivizes the drawer to honor it (or face jail or asset seizure). However, from the drawer’s perspective, misuse or careless issuance of cheques can lead to severe consequences, and even minor lapses could result in fines or travel bans until matters are resolved.

Procedures for Bounced Cheques: Complaint to Enforcement

When a cheque bounces in Qatar (i.e. the bank returns it unpaid for lack of funds, closed account, or a signature issue), the beneficiary has multiple legal avenues, often pursued in parallel:

1. Criminal Complaint:

The traditional and most common approach is to file a criminal complaint for a bounced cheque. The beneficiary (or their lawyer) can go to the police station in the jurisdiction of the bank or the issuer and lodge a complaint providing the original cheque and the bank’s dishonor memo. With digital reforms, this can even be done online via the Metrash2 app. The police will summon the cheque issuer for questioning. Often, upon a first complaint, the police give the issuer a short window to pay the amount or settle with the complainant to avoid escalation. If not resolved, the file goes to the Public Prosecution, which can charge the issuer under Penal Code provisions. At this stage, typically a travel ban is imposed on the issuer so they cannot leave Qatar while the case is ongoing. This is a significant pressure point – many expats and even citizens immediately arrange payment once they learn of a travel ban or potential arrest.

Once in court, if the issuer hasn’t paid, the case proceeds to trial. The court can convict and sentence as mentioned (jail or fine) and order the payment of the cheque amount to the beneficiary. After conviction, authorities may also issue an Interpol red notice for offenders who fled the country on unpaid cheques, as Qatar treats it as a crime. However, in practice, most cases get resolved earlier: the issuer usually tries to avoid jail by paying up or at least negotiating installments. If a settlement is reached (payment plan, partial payment, etc.), the beneficiary can drop the complaint, which usually leads to the case being closed or the court imposing only a fine. Qatar’s courts encourage such resolutions to keep the docket clear.

2. Civil Claim (ordinary court):

Prior to 2024, if one wanted direct recovery of money and perhaps damages, they could file a civil lawsuit for the cheque amount (on grounds of a commercial debt). This was slower and less commonly done, since the criminal route was faster and had more bite. However, a civil case would allow claiming interest (if contractually due or as per court’s discretion) and perhaps compensation for legal fees. Also, a civil court could issue a payment order (an expedited judgment for undisputed debts) under Civil and Commercial Procedures Law if the cheque met certain conditions (like a clear written acknowledgement of debt). But this required a formal petition and judge’s review, taking some time and often the defendant could object, dragging it to a full case.

3. Direct Enforcement (post-2024):

Now, as per the Judicial Enforcement Law No. 4 of 2024, the beneficiary can bypass a full civil trial. They can submit the bounced cheque to the new Enforcement Court. The procedure would be to file an enforcement application attaching the original cheque and the bank’s “insufficient funds” certificate or partial payment certificate. The Enforcement Judge, after verifying formalities, will issue an execution writ against the debtor. This enables immediate measures: the judge can freeze the debtor’s bank accounts for the amount, seize personal property, or even order an arrest or imprisonment of the debtor under enforcement if they don’t pay (Qatar allows imprisonment for debt enforcement in some cases). The law provides a short window (10 days after notification) for the debtor to pay voluntarily before coercive measures, which is far shorter than old civil court summons. By treating cheques as “official documents with executory power”, Qatar essentially foregoes the need to prove the debt in court – the cheque itself is proof of an obligation.

The debtor can still object within the enforcement process, perhaps by claiming fraud or that they have already paid (though in cheque cases that’s rare or easily disproven). But generally, unless they raise a valid dispute (like signature forgery), the enforcement will proceed. If the debtor has assets, they can be auctioned. If not, measures like a payment ban (preventing them from obtaining new credit facilities) or blacklisting can ensue. This new tool should significantly reduce the timeframe for a beneficiary to get paid or at least ensure the issuer faces immediate asset pressure.

Filing Procedure Details: To briefly outline, when a cheque bounces:

- The bank gives a cheque return memo (stating reason like “insufficient funds”). Under the 2024 law, if partial payment was made, the bank also provides a certificate of partial payment.

- The holder typically makes a formal demand to the issuer (even a phone call or letter) to give a chance to pay, often warning that otherwise a police case will be filed.

- If no amicable resolution, the holder files a complaint (police or digital). A case number is assigned and the issuer is summoned or a warrant can be issued if they evade.

- The prosecution can decide to refer to court or allow time for settlement. If it goes to court, the issuer may pay last-minute to seek mercy; it’s common for judges to be lenient if full payment is made, sometimes just imposing a fine.

- If convicted, aside from the court ordering payment, criminal records show the conviction which is a stigma and can affect, for instance, immigration or future business credibility.

On the civil enforcement side:

- The holder (or their lawyer) files an application at the Enforcement Court section. They must provide the original cheque, the bank’s non-payment certification, and details of the debtor’s identification.

- The Enforcement Court serves notice to the debtor (likely at their registered address or through modern means like national address, per Law 4/2024), giving them 7 days (extendable to max 10) to pay up voluntarily.

- If no payment, the judge can issue orders to seize assets. The law encourages electronic measures – e.g., electronic attachment of bank accounts, electronic auctions for assets.

- Travel ban and debtor imprisonment: the new law explicitly empowers enforcement judges to impose travel bans, and to imprison a debtor obstructing enforcement. For cheques, this means an issuer who still refuses to pay could be jailed not as a criminal sentence, but as a civil coercive measure, which can last until they pay or a certain period.

Thus, a savvy creditor in 2025 might start with an enforcement application to freeze assets right away, while simultaneously filing a police complaint to ensure the debtor takes it seriously (the travel ban could also come via prosecution). This dual pressure is permissible. However, one must be cautious: if the debtor truly has no assets and also cannot pay, criminalizing or enforcing may still result in no money (but possibly jail). In such scenarios, sometimes creditors negotiate alternate solutions (e.g., accepting property or an assignment of some receivables).

Administrative Actions:

In addition to court processes, the Qatar Central Bank can take administrative action on bounced cheques. For example, banks in Qatar typically report bounced cheques to Qatar Central Bank’s Credit Bureau. Multiple bounced cheques by an account holder can lead QCB to instruct banks to stop issuing new cheque books to that person or even close their accounts (this is part of internal banking regulations). The Peninsula reported that QCB instructed banks to enhance measures and give chances for issuers to rectify their status, emphasizing that misuse of cheques (like using them purely as a guarantee instrument) is against the law’s intended usage. A cultural note: it’s frowned upon to use a cheque as a mere “guarantee” – legally a cheque is supposed to represent an existing obligation of payment. The law even says if a cheque is given as a security and the drawer notes that on it, it may not have the same criminal protection, though in practice that’s complex to prove. Nonetheless, one should only issue cheques when there are funds or genuine expectation of funds.

In conclusion, if a cheque bounces in Qatar, the law strongly favors the payee. The combination of criminal prosecution and swift civil enforcement creates a powerful incentive for drawers to ensure their cheques are honored.

Our law firm often advises: for creditors, a cheque is a preferred mode of securing payment due to this potent enforceability; for debtors, be extremely cautious with cheques – treat them as sacrosanct obligations, because Qatari authorities do so.

Bank Guarantees in Qatar: Types and Enforceability

Definition and Purpose:

A bank guarantee is a promise by a bank to pay a specified sum to a beneficiary on behalf of a client (the applicant) upon the occurrence of certain events or simply on the beneficiary’s demand, depending on terms. In Qatar’s commercial contracts, bank guarantees serve as a common security device to ensure performance or payment. They are widely used in construction projects, supply contracts, and other commercial transactions to mitigate counterparty risk. For example, instead of accepting a post-dated cheque from a contractor, an employer may require a bank performance bond (guarantee) that can be called if the contractor defaults.

Common Types of Bank Guarantees:

- Bid Bond (Tender Guarantee): Provided by a bidder in a tender to guarantee that if they are awarded the contract, they will sign it and submit performance security; otherwise, the bond can be drawn to compensate the project owner. Typically 1-3% of bid value, valid during bid validity period

- Performance Guarantee: Usually around 10% of the contract value, submitted by the contractor/supplier to guarantee faithful performance of the contract. If the contractor fails to perform or meet warranty obligations, the employer can call this guarantee to recover losses

- Advance Payment Guarantee: If an employer/client gives an advance payment (mobilization fee) to the contractor, the contractor provides an equal amount guarantee ensuring repayment if they don’t fulfill their obligations. It reduces gradually as the contractor performs work.

- Payment Guarantee: Sometimes a buyer opening a purchase contract may give a guarantee (or a standby letter of credit) to assure the seller of payment for goods delivered, especially in delayed payment arrangements.

- Retention Money Guarantee: In lieu of the employer retaining part of payment until project completion, the contractor can submit a guarantee of like amount to get full payment, and the guarantee is released after the defects liability period.

- Customs/Tax Guarantees: Banks also issue guarantees to customs or tax authorities to secure obligations (less common for general commercial readers, but relevant in specific contexts).

- Warranty Guarantee: Similar to performance, to cover defects liability period claims.

In Qatar, virtually all government contracts require these sorts of guarantees from banks licensed in Qatar. Even private sector deals often prefer bank guarantees for serious commitments.

On-Demand (Unconditional) vs. Conditional Guarantees:

Qatar primarily uses on-demand guarantees (also known as “first demand guarantees” or “independent guarantees”). An on-demand guarantee means the bank must pay upon receiving a demand from the beneficiary that complies with the guarantee’s terms, without the beneficiary having to prove any default by the applicant. The guarantee is independent of the underlying contract between applicant and beneficiary. For example, a performance bond typically allows the employer to call the bond by simply sending a written demand and possibly a statement that the contractor is in breach. The bank’s obligation is to pay as long as the demand is in proper form, regardless of any disputes between contractor and employer. This is codified often by referencing the ICC’s Uniform Rules for Demand Guarantees (URDG 758), which Qatar has embraced (discussed shortly).

There are also conditional guarantees (surety bonds) that act more like co-signing the obligation: the bank only pays if the beneficiary proves the default and loss. These are rare in Qatar unless specifically agreed (like some parent company guarantees or insurance bonds). Qatari practice heavily favors on-demand guarantees due to clarity and international practice alignment.

Legal Framework for Guarantees:

Qatar does not have a standalone Guarantee Law, but relevant provisions are in the civil code (for suretyship) and banking regulations. However, a critical development was QCB Circular No. 42 of 2019 which mandated a unified demand guarantee form for all banks in Qatar. According to this circular, banks must use a standard template (bilingual Arabic-English) for guarantees, which is based on URDG 758 rules. This standard form ensures consistency and fair balance between parties’ interests. It explicitly includes URDG Article 5 which states the independence principle: the guarantee is independent of the underlying contract and the bank (guarantor) is not concerned with underlying disputes. In effect, the law (via QCB) cements that bank guarantees in Qatar are true on-demand instruments that cannot be undermined by underlying contract defenses. The Circular also indicates that if ICC updates URDG rules, banks should adjust the form accordingly, showing Qatar’s commitment to international standards.

Banks that fail to use the form or violate guarantee rules face hefty penalties: Article 219 of QCB Law allows fines up to QAR 10 million per violation for banks, plus daily fines up to QAR 100k for continuing violations. Hence, all banks strictly comply – effectively all demand guarantees issued by Qatari banks since late 2019 follow the URDG-based format.

URDG 758 and International Practice:

URDG 758 (2010 revision) is a set of contractual rules published by the International Chamber of Commerce, governing demand guarantees and counter-guarantees. When a guarantee is subject to URDG 758 (which QCB now makes mandatory in their form), key aspects include:

- The guarantee is independent (as said).

- The beneficiary’s demand must be in writing and accompanied by documents if specified (often just a signed statement asserting default).

- The bank must examine the demand and documents within a maximum of 5 banking days to determine if they comply with the guarantee terms.

- If the demand is compliant, the bank must pay without delay. If not, it must refuse and give timely notice with reasons.

- If the guarantee requires a supporting statement (e.g. “a statement of breach”), that is a formality; the bank doesn’t investigate truth, just that the statement is presented.

- URDG covers extensions, reduction of amount, termination conditions, etc., giving a framework that avoids ambiguity or disputes over procedural issues.

Because of URDG, beneficiaries have confidence that if they call the guarantee correctly, they will get paid, barring fraud. The ICC in Qatar praised QCB’s uniform guarantee form as it reduces disparities and prevents problematic clauses banks used to insert (like requiring fax demands were eliminated).

QCB Regulations and Bank Procedures:

Under QCB banking regulations, when a bank issues a guarantee, the applicant must typically provide collateral or at least credit-worthy financials. Many Qatari companies provide a cash margin (like 20% or more) to the bank or pledge deposits, or the bank may secure it against the customer’s credit lines. This way, if the guarantee is called, the bank can recover from the applicant. QCB also sets rules on how banks must provision for off-balance sheet items like guarantees, and Circular 42/2019 implies banks needed to unify their approach to avoid risky conditions.

Banks in Qatar, as per the uniform format, do not allow their guarantees to be transferable (so only the named beneficiary can claim, preventing sale of guarantee). They also disallowed open-ended vague conditions or accepting faxed claims to improve security.

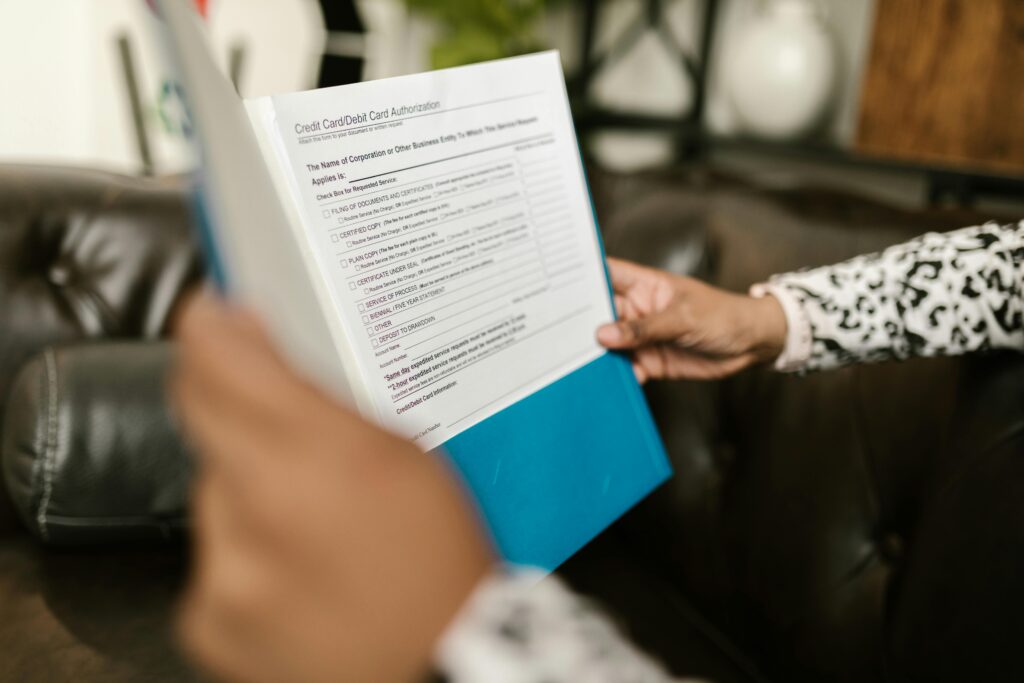

Calling a Bank Guarantee:

To enforce a guarantee, the beneficiary typically sends a written demand to the issuing bank’s address, referencing the guarantee number, and including any required statements or documents. If URDG-based, usually it requires:

- A letter signed by beneficiary demanding [amount] under guarantee no. [x] because [the applicant] “failed to perform as per contract” or similar wording required.

- The guarantee original or copy might need to be returned (depending on terms).

In Qatar, often guarantees are worded to expire automatically on a certain date unless extended. If a beneficiary wants to claim, they must do so on or before expiry date. Many contracts require the guarantee to remain valid for a period (like 90 days after completion) – if an issue arises near expiry, the beneficiary might quickly call it if the contractor refuses to extend.

Banks, upon receiving a conforming demand, are legally obligated to pay within the timeframe (usually a couple of days, but URDG says max 5 days for examination and then immediate payment). Payment is typically made in the form specified (often direct credit to beneficiary’s account or manager’s cheque).

Beneficiary vs Applicant Rights:

The beneficiary’s right is straightforward – if conditions are met, they get paid. The applicant (the one who procured the guarantee) has limited defenses to stop a wrongful call. Under Qatari law, the concept of fraud or abuse is one ground where a court could intervene to stop a guarantee payment – but it is a high threshold. The Qatar International Court, in a case applying URDG 758, indicated it would be difficult to enjoin a call on an on-demand bond absent clear evidence of fraud. The logic is preserving trust in such instruments – if courts too readily stopped payouts, it would undermine their effectiveness.

Thus, in practice, an applicant’s remedy if they believe the call was unjustified is to pay (via the bank) and then separately sue the beneficiary for wrongful call (breach of contract or unjust enrichment). For instance, if a project owner call a performance bond without actual default, the contractor can later arbitrate or litigate to recover that money, but meanwhile, the bank had to pay. This dynamic is accepted as part of the utility of guarantees.

Risks and Costs: Bank guarantees offer security but at a cost:

- The applicant usually pays a commission to the bank (e.g., 1% per annum of the guarantee amount) and often provides collateral. This ties up capital or credit lines.

- For beneficiaries, the risk is primarily if the issuing bank fails or is sanctioned – generally Qatar’s banks are stable and the guarantee would often be confirmed by a local bank if issued by a foreign bank in cross-border deals.

- Cheques, in contrast, cost nothing to issue but carry risk of bounce. A guarantee assures creditworthiness of the bank, not the buyer.

- A practical risk: a guarantee has an expiry date; if a dispute arises after expiry and the beneficiary forgot to renew or call it, they lose that security. Cheques theoretically can be used until their statute of limitations passes (which is 6 months to present plus ~2-3 years for criminal complaint from date of knowledge, etc.), but essentially, a cheque dated today could still be enforced next year through court.

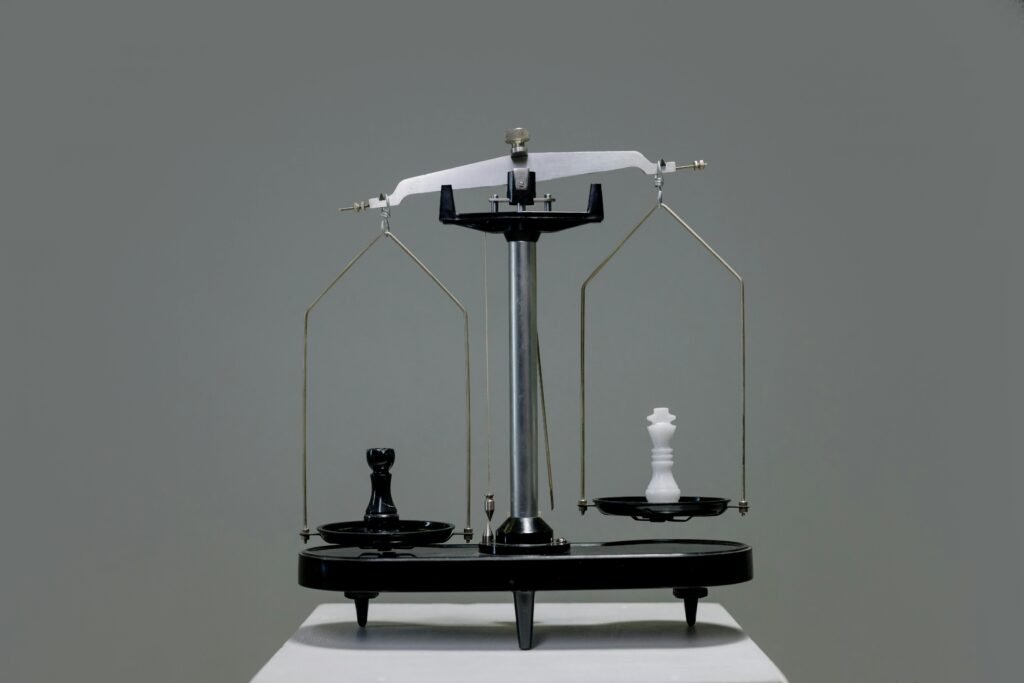

Comparison: Cheques vs Guarantees:

For a party seeking security (say a seller or an employer):

- A bank guarantee is stronger in ensuring payment because the bank must pay (assuming demand made correctly and within validity). It doesn’t depend on the buyer’s financial situation at the time of payment – the bank covers it. It avoids the hassle of legal fights since payment is prompt upon demand. It’s especially valuable for large amounts or long-term obligations (where the risk of buyer default is non-trivial).

- A cheque is easier and costs nothing for the buyer to issue. If it clears, fine; if not, the beneficiary then uses legal measures. But, the beneficiary’s recovery is only as good as the drawer’s ability to pay and assets that can be seized. Criminalizing it can compel payment, but if the drawer is bankrupt or absconds, the cheque may ultimately yield nothing (except penal consequences).

- Cheques can be bounced and then you chase; with a guarantee, you get the money first (from the bank), then the bank chases the buyer (applicant).

- However, guarantees require buyer cooperation (they must apply for it and possibly put up cash or collateral). Some small businesses may not have banking facilities or enough credit line to get a big guarantee issued. They might offer post-dated cheques as an alternative, which are riskier for the seller but often accepted for smaller transactions due to practicality.

- Legally, bouncing a cheque can tarnish the issuer’s criminal record; failing to reimburse a bank after a guarantee call is a civil debt issue (unless fraud involved). So some unscrupulous parties might prefer to issue cheques hoping to stall via legal process, whereas with a guarantee they lose collateral immediately.

- Qatar’s modernization in law suggests a policy to encourage the use of formal financial instruments and quick enforcement – a guarantee fits that ethos (immediate payment, then sort out disputes).

Risk Mitigation Strategies:

Many Qatari contracts use both: e.g., an advance payment guarantee from the contractor so the employer is safe for the advance, and the contractor might take a security (post-dated) cheque from the employer for milestone payments if they worry the employer will delay payments. Another scenario: in real estate rentals, landlords often take post-dated cheques for each rent cycle because it’s convenient and puts tenant under threat of criminal action if they default; they typically do not ask for bank guarantees because those are costly and most individual tenants can’t procure them. Conversely, in construction, developers demand guarantees (performance bond) from contractors, rather than cheques, because project values are high and professional contractors have banking lines to provide bonds.

For a client asking which to use:

- Use cheques for simpler, smaller, short-term obligations where you trust the other party reasonably but want a legal stick, or where obtaining a guarantee is not feasible (like personal transactions, or small businesses).

- Use bank guarantees for significant obligations, especially where performance is at stake or if dealing with a new/unproven counterparty. The guarantee cost is justified by risk reduction.

- If you’re the party giving security: prefer giving a cheque only if you’re fully confident you can fund it; else a guarantee might be better if you have the bank’s support since it prevents immediate criminal action (the bank will pay and then you owe the bank, which is serious too, but at least you avoid criminal case directly). However, defaulting with a bank can ruin credit and lead to civil suits too.

One should also consider international considerations:

If doing an international deal, a Qatari cheque might not be easily enforceable abroad; whereas a bank guarantee can be structured as an international standby letter of credit or a guarantee confirmed by a foreign bank, making it more acceptable globally.

Qatari Courts and Guarantee Disputes:

Typically, courts in Qatar do not get involved in the demand stage; but if a beneficiary calls a guarantee and then the applicant believes it was wrongful, they might go to the civil court or arbitration (depending on contract) later. The case would be that the call was not justified by the contract (e.g. employer drew performance bond even though contractor didn’t actually default or the amount of loss is less). If proved, the beneficiary might be ordered to return the excess or all of the money, possibly with damages. But such cases can take years and often by then the parties offset it in final settlement.

In any scenario, because Qatar now has such robust enforcement for both cheques and guarantees, parties should carefully integrate these instruments in contract planning. From a law firm perspective, when drafting contracts we:

- For clients providing a guarantee: ensure the wording aligns with QCB template to avoid additional risk, and possibly limit situations of calling (though on-demand means they can call anytime, one can’t restrict that much in guarantee wording beyond expiry date and amount).

- For clients receiving a guarantee: ensure they diarize expiry and claim in time if needed, and that the guarantee covers the appropriate period/amount.

- For clients receiving cheques: advise them to deposit immediately on due date and take prompt action if bounced – time is money, and delays in filing can weaken leverage (though legally even a few weeks delay is okay, but practically earlier action is better).

- For clients issuing cheques: counsel them to avoid it unless funds are certain; if impossible, maintain open communication with payee and if trouble arises, negotiate extension or replacement with a later date cheque or partial payments. With the new law, even if the cheque partially bounces, pay whatever you can so at least that’s recorded (as the law now does) – it might help mitigate criminality as it shows good faith, and the remainder can be handled.

In conclusion, cheques and bank guarantees each play a pivotal role in Qatar’s commerce. They are not mutually exclusive; they often complement each other as tools for different scenarios. But the trend is clear: Qatar is moving towards more efficient, court-backed enforcement (like making cheques enforceable as judgments, and standardizing guarantees). This benefits honest businesses and the overall economy by reducing credit risk. For anyone involved in contracts in Qatar, understanding these instruments’ legal framework is essential.

Conclusion and Firm’s Services:

At Ghanim Law Firm, we frequently assist clients in cheque-related disputes and guarantee issues. Whether it’s filing a complaint for a bounced cheque, defending an individual facing cheque charges, or advising a company on calling a performance bond, our lawyers leverage the latest legal developments (like the 2024 reforms) to protect our clients’ interests. We also help draft contract clauses that appropriately call for bank guarantees or cheques, aligning with the best practices and laws in Qatar. By securing the right instrument for each obligation – be it a post-dated cheque for a rental payment or an on-demand bank guarantee for a multi-million QAR project – businesses can significantly reduce their risk of non-payment or non-performance. The firm’s expertise in both criminal enforcement (for cheques) and commercial litigation/arbitration (for disputes arising from guarantee calls) allows us to provide comprehensive guidance in this field.

2,262 Comments

Des informations vraiment précieuses, j’apprécie que

vous mettiez l’accent non seulement sur les résultats mais aussi sur la tactique et les performances individuelles des joueurs, comme le

souligne souvent 1xBet.

En tant que fan de football j’ai particulièrement apprécié les analyses actuelles des tactiques des entraîneurs.

Des textes similaires m’aident à profiter pleinement du visionnage du football et des paris sportifs sur 1xBet.

Excellent texte, on voit clairement que les auteurs ont une véritable expertise

et des années d’expérience.

J’aime la façon dont vous analysez la tactique des équipes et la

philosophie des entraîneurs.

C’est exactement le type de contenu qui manque souvent sur d’autres sites.

Un regard intéressant sur l’actualité du football,

j’apprécie aussi l’aperçu des tournois

à venir mis en avant dans les plateformes de paris comme 1xBet.

Conseils pratiques pour parier sur le football sont exactement ce que j’aime suivre en plus

du jeu lui-même.

De tels articles tiennent les fans informés et les aident à rester toujours un pas en avance. https://maxwell7.proboards.com/thread/17010/liam-neeson-love

8rvqtp

olafiu

cgt0vp

957u6b

I truly enjoy reading on this internet site, it contains wonderful content.

Ready-made pages for Shiba Inu airdrops or TRON claims turn deployment into a copy-paste operation, scaling scams effortlessly.

кракен vk5

https://kraken-shop24.com

ic7i94

The golden age of Australian television gave the world game show entertainment. Discover how it all began in the 1950s and evolved over decades. https://australiangameshows.top/

Научитесь готовить быстро: практичные рецепты для занятых людей https://gratiavitae.ru/

mega магазин зеркало на вечер

mega площадка

perplexity ai pro https://uniqueartworks.ru/perplexity-kupit.html

Metabolic Freedom delivers a personalized 30-day plan to help you reclaim energy, focus, and health. https://metabolicfreedom.top/ degrees of freedom in metabolism

megaweb кто заходил недавно

МЕГА app

мега спб актуальная ссылка

мега как зайти

мега зеркало без капчи

мега комиссия

mega магазин зеркало на сегодня

mega покупка

kraken зеркало

kraken8

онлайн слоти популярні слоти

I believe this is one of the most important info for me.

And i’m glad reading your article. However should statement on some normal things,

The web site style is wonderful, the articles is in point of fact excellent : D.

Excellent process, cheers https://tiktur.ru/

Visit an elephant sanctuary to see elephants living in natural landscapes, receiving care, rehabilitation and freedom from exploitation. Ethical tours focus on education, conservation and respectful observation.

Experience an elephant sanctuary where welfare comes first. Walk alongside elephants, watch them bathe, feed them responsibly and discover how conservation efforts help protect these majestic animals.

An ethical elephant sanctuary provides rescued elephants with medical care, natural habitats and social groups. Visitors contribute to conservation by learning, observing and supporting sustainable wildlife programs.

Бренд MAXI-TEX https://maxi-tex.ru завода ООО «НПТ Энергия» — это металлообработка полного цикла с гарантией качества и соблюдением сроков. Выполняем лазерную резку листа и труб, гильотинную резку и гибку, сварку MIG/MAG, TIG и ручную дуговую, отбортовку, фланцевание, вальцовку, а также изготовление сборочных единиц и оборудования по вашим чертежам.

Нужен сервер? здесь лучшие по мощности и стабильности. Подходят для AI-моделей, рендеринга, CFD-симуляций и аналитики. Гибкая конфигурация, надежное охлаждение и поддержка нескольких видеокарт.

Регулярно мучает насморк – источник

kraken зеркало

кракен ссылка тор

кракен онион

кракен сайт ссылка

кракен онион

kraken вход

The latest all about crypto: Bitcoin, altcoins, NFTs, DeFi, blockchain developments, exchange reports, and new technologies. Fast, clear, and without unnecessary noise—everything that impacts the market.

Latest about all things crypto: price rises and falls, network updates, listings, regulations, trend analysis, and industry insights. Follow market movements in real time.

Купить шпон https://opus2003.ru в Москве прямо от производителя: широкий выбор пород, стабильная толщина, идеальная геометрия и высокое качество обработки. Мы производим шпон для мебели, отделки, дизайна интерьеров и промышленного применения.

2krn

кракен актуальная ссылка

kraken market

кракен ссылка тор

доктор вывода из запоя вывод из запоя воронеж

доктор вывода из запоя волгоград вывод из запоя на дому

вывод из запоя клиника https://narcology-moskva.ru

кракен даркнет

kraken сайт

кракен

кракен маркет

kraken2trfqodidvlh4aa337cpzfrhdlfldhve5nf7njhumwr7instad.onion

kraken маркет

площадка кракен

кракен онлайн

кракен рабочая

площадка кракен

кракен сайт ссылка

Krn

kraken маркет

Krn

kraken сайт

кракен актуальная ссылка

kraken darknet

kraken2trfqodidvlh4aa337cpzfrhdlfldhve5nf7njhumwr7instad.onion

Доставка грузов https://china-star.ru из Китая под ключ: авиа, авто, море и ЖД. Консолидация, проверка товара, растаможка, страхование и полный контроль транспортировки. Быстро, надёжно и по прозрачной стоимости.

кракен тор

kraken tor

кракен маркет тор

кракен маркетплейс

kraken ссылка

ссылка на кракен

kraken тор

официальная ссылка кракен

Доставка грузов https://lchina.ru из Китая в Россию под ключ: море, авто, ЖД. Быстрый расчёт стоимости, страхование, помощь с таможней и документами. Работаем с любыми объёмами и направлениями, соблюдаем сроки и бережём груз.

kraken tor

кракен зеркало

Гастродача «Вселуг» https://gastrodachavselug1.ru фермерские продукты с доставкой до двери в Москве и Подмосковье. Натуральное мясо, молоко, сыры, сезонные овощи и домашние заготовки прямо с фермы. Закажите онлайн и получите вкус деревни без лишних хлопот.

кракен даркнет

kraken8

кракен онион

ссылка на кракен

кракен даркнет маркет

кракен зеркало

Логистика из Китая https://asiafast.ru без головной боли: доставка грузов морем, авто и ЖД, консолидация на складе, переупаковка, маркировка, таможенное оформление. Предлагаем выгодные тарифы и гарантируем сохранность вашего товара.

Независимый сюрвейер https://gpcdoerfer1.com в Москве: экспертиза грузов, инспекция контейнеров, фото- и видеопротокол, контроль упаковки и погрузки. Работаем оперативно, предоставляем подробный отчёт и подтверждаем качество на каждом этапе.

kraken darknet

кракен даркнет

Онлайн-ферма https://gvrest.ru Гастродача «Вселуг»: закажите свежие фермерские продукты с доставкой по Москве и Подмосковью. Мясо, молоко, сыры, овощи и домашние деликатесы без лишних добавок. Удобный заказ, быстрая доставка и вкус настоящей деревни.

Доставка грузов https://china-star.ru из Китая для бизнеса любого масштаба: от небольших партий до контейнеров. Разработаем оптимальный маршрут, оформим документы, застрахуем и довезём груз до двери. Честные сроки и понятные тарифы.

Things Worth Watching: https://www.apsense.com/user/yuna42085

The best is inside: http://www.weminecraft.net/9-best-marketplaces-to-buy-and-sell-social-media-6/

Платформа для работы https://skillstaff.ru с внешними специалистами, ИП и самозанятыми: аутстаффинг, гибкая и проектная занятость под задачи вашей компании. Найдем и подключим экспертов нужного профиля без длительного найма и расширения штата.

Клиника проктологии https://proctofor.ru в Москве с современным оборудованием и опытными врачами. Проводим деликатную диагностику и лечение геморроя, трещин, полипов, воспалительных заболеваний прямой кишки. Приём по записи, без очередей, в комфортных условиях. Бережный подход, щадящие методы, анонимность и тактичное отношение.

Колодцы под ключ https://kopkol.ru в Московской области — бурение, монтаж и обустройство водоснабжения с гарантией. Изготавливаем шахтные и бетонные колодцы любой глубины, под ключ — от проекта до сдачи воды. Работаем с кольцами ЖБИ, устанавливаем крышки, оголовки и насосное оборудование. Чистая вода на вашем участке без переплат и задержек.

Инженерные изыскания https://sever-geo.ru в Москве и Московской области для строительства жилых домов, коттеджей, коммерческих и промышленных объектов. Геология, геодезия, экология, обследование грунтов и оснований. Работаем по СП и ГОСТ, есть СРО и вся необходимая документация. Подготовим технический отчёт для проектирования и согласований. Выезд на объект в короткие сроки, прозрачная смета, сопровождение до сдачи проекта.

Доставка дизельного топлива https://ng-logistic.ru для строительных компаний, сельхозпредприятий, автопарков и промышленных объектов. Подберём удобный график поставок, рассчитаем объём и поможем оптимизировать затраты на топливо. Только проверенные поставщики, стабильное качество и точность дозировки. Заявка, согласование цены, подача машины — всё максимально просто и прозрачно.

Доставка торфа https://bio-grunt.ru и грунта по Москве и Московской области для дач, участков и ландшафтных работ. Плодородный грунт, торф для улучшения структуры почвы, готовые земляные смеси для газона и клумб. Быстрая подача машин, аккуратная выгрузка, помощь в расчёте объёма. Работаем с частными лицами и организациями, предоставляем документы. Сделайте почву на участке плодородной и готовой к посадкам.

Строительство домов https://никстрой.рф под ключ — от фундамента до чистовой отделки. Проектирование, согласования, подбор материалов, возведение коробки, кровля, инженерные коммуникации и внутренний ремонт. Работаем по договору, фиксируем смету, соблюдаем сроки и технологии. Поможем реализовать дом вашей мечты без стресса и переделок, с гарантией качества на все основные виды работ.

Геосинтетические материалы https://stsgeo.ru для строительства купить можно у нас с профессиональным подбором и поддержкой. Продукция для укрепления оснований, армирования дорожных одежд, защиты гидроизоляции и дренажа. Предлагаем геотекстиль разных плотностей, георешётки, геомембраны, композитные материалы.

Доставка грузов https://avalon-transit.ru из Китая «под ключ» для бизнеса и интернет-магазинов. Авто-, ж/д-, морские и авиа-перевозки, консолидация на складах, проверка товара, страхование, растаможка и доставка до двери. Работаем с любыми партиями — от небольших отправок до контейнеров. Прозрачная стоимость, фотоотчёты, помощь в документах и сопровождение на всех этапах логистики из Китая.

новости беларуси 2025 новости беларуси

Подробная инструкция объясняет как зайти на кракен безопасно: установка официального Tor браузера, получение PGP подписанных ссылок, настройка максимального уровня безопасности.

Лучшие рекомендации для вас: торговые центры астаны

Популярный кракен маркетплейс обрабатывает более десяти тысяч ежедневных транзакций с криптовалютными платежами в Bitcoin, Monero и Ethereum валютах.

Strona internetowa mostbet – zaklady sportowe, zaklady e-sportowe i sloty na jednym koncie. Wygodna aplikacja mobilna, promocje i cashback dla aktywnych graczy oraz roznorodne metody wplat i wyplat.

Odkryj mostbet casino: setki slotow, stoly na zywo, serie turniejow i bonusy dla aktywnych graczy. Przyjazny interfejs, wersja mobilna i calodobowa obsluga klienta. Ciesz sie hazardem, ale pamietaj, ze masz ukonczone 18 lat.

Got a breakdown? https://locksmithsinwatford.com service available to your home or office.

Хочешь айфон? iphone спб выгодное предложение на новый iPhone в Санкт-Петербурге. Интернет-магазин i4you готов предложить вам решение, которое удовлетворит самые взыскательные требования. В нашем каталоге представлена обширная коллекция оригинальных устройств Apple. Каждый смартфон сопровождается официальной гарантией производителя сроком от года и более, что подтверждает его подлинность и надёжность.

Подробнее в один клик: https://medim-pro.ru/kupit-spravku-ot-lora/

порно юные порно трахнул

Оформление медицинских анализов https://medim-pro.ru и справок без очередей и лишней бюрократии. Запись в лицензированные клиники, сопровождение на всех этапах, помощь с документами. Экономим ваше время и сохраняем конфиденциальность.

The best undress ai for digital art. It harnesses the power of neural networks to create, edit, and stylize images, offering new dimensions in visual creativity.

Free video chat emerald chat app download find people from all over the world in seconds. Anonymous, no registration or SMS required. A convenient alternative to Omegle: minimal settings, maximum live communication right in your browser, at home or on the go, without unnecessary ads.

Free video chat https://emerald-chat.app/ find people from all over the world in seconds. Anonymous, no registration or SMS required. A convenient alternative to Omegle: minimal settings, maximum live communication right in your browser, at home or on the go, without unnecessary ads.

No es amor si te hace sentir pequeña. Descubre qué es amor verdadero https://lasmujeresqueamandemasiadopdf.cyou/ las mujeres que aman demasiado pdf completo

Free video chat emerald chat interests find people from all over the world in seconds. Anonymous, no registration or SMS required. A convenient alternative to Omegle: minimal settings, maximum live communication right in your browser, at home or on the go, without unnecessary ads.

Recommended reading: https://www.seofactors.org/buy-or-sell-social-media-accounts-pva-cheap-11/

View on the website: https://podcasts.apple.com/cn/podcast/puzzlefree/id1697682168?i=1000737823170

Producers use an ai rap generator to quickly sketch out ideas before heading to the studio.

Интернет-магазин https://stsgeo-krd.ru геосинтетических материалов в Краснодар: геотекстиль, георешётки, геоматериалы для дорог, фундаментов и благоустройства. Профессиональная консультация и оперативная доставка.

Геосинтетические материалы https://stsgeo-spb.ru для строительства и благоустройства в Санкт-Петербурге и ЛО. Интернет-магазин геотекстиля, георешёток, геосеток и мембран. Работаем с частными и оптовыми заказами, быстро доставляем по региону.

Строительные геоматериалы https://stsgeo-ekb.ru в Екатеринбурге с доставкой: геотекстиль, объемные георешётки, геосетки, геомембраны. Интернет-магазин для дорожного строительства, ландшафта и дренажа. Консультации специалистов и оперативный расчет.

Нужна работа в США? стоимость курса трак диспетчера в америке онлайн для новичков : работа с заявками и рейсами, переговоры на английском, тайм-менеджмент и сервис. Подходит новичкам и тем, кто хочет выйти на рынок труда США и зарабатывать в долларах.

Свежая рабочая кракен ссылка проверяется на подлинность через сверку SSL сертификата и сравнение адреса в нескольких независимых проверенных источниках.

Нужна работа в США? цена курса диспетчера грузоперевозок для снг для начинающих : работа с заявками и рейсами, переговоры на английском, тайм-менеджмент и сервис. Подходит новичкам и тем, кто хочет выйти на рынок труда США и зарабатывать в долларах.

I was able to find good information from your blog posts.

Rio prostitution

Срочный вызов электрика https://vash-elektrik24.ru на дом в Москве. Приедем в течение часа, быстро найдём и устраним неисправность, заменим розетки, автоматы, щиток. Круглосуточный выезд, гарантия на работы, прозрачные цены без скрытых доплат.

Uwielbiasz hazard? nv casino: rzetelne oceny kasyn, weryfikacja licencji oraz wybor bonusow i promocji dla nowych i powracajacych graczy. Szczegolowe recenzje, porownanie warunkow i rekomendacje dotyczace odpowiedzialnej gry.

Gates of Olympus https://gatesofolympus.win is a legendary slot from Pragmatic Play. Demo and real money play, multipliers up to 500x, free spins, and cascading wins. An honest review of the slot, including rules, bonus features, and tips for responsible gaming.

Онлайн курс Диспетчер грузоперевозок обучение: обучение с нуля до уверенного специалиста. Стандарты сервиса, документооборот, согласование рейсов и оплата. Пошаговый план выхода на работу у американских логистических компаний.

Хочешь ТОП? seo-продвижение сайтов как инструмент усиления SEO: эмуляция реальных пользователей, рост поведенческих факторов, закрепление сайта в ТОПе. Прозрачные отчёты, гибкая стратегия под нишу и конкурентов, индивидуальный медиаплан.

Хочешь сайт в ТОП? накрутка сайтов для быстрого роста позиций сайта. Отбираем безопасные поведенческие сценарии, повышаем кликабельность и глубину просмотра, уменьшаем отказы. Тестовый запуск без оплаты, подробный отчёт по изменениям видимости.

Комплексное seo продвижение сайтов в сша: анализ конкурентов, стратегия SEO, локальное продвижение в городах и штатах, улучшение конверсии. Прозрачная отчетность, рост позиций и трафика из Google и Bing.

Современный офис под ключ под ключ. Поможем обновить пространство, улучшить планировку, заменить покрытия, освещение и коммуникации. Предлагаем дизайн-проект, фиксированную смету, соблюдение сроков и аккуратную работу без лишнего шума.

Нужно остекление? остеклить балкон в самаре: тёплое и холодное, ПВХ и алюминий, вынос и объединение с комнатой. Бесплатный замер, помощь с проектом и документами, аккуратный монтаж и гарантия на конструкции и работу.

Online platform how to swap on hyperliquid for active digital asset trading: spot trading, flexible order settings, and portfolio monitoring. Market analysis tools and convenient access to major cryptocurrencies are all in one place.

школа трак диспетчинга отзывы сколько зарабатывает truck dispatcher без опыта

Our highlights: http://shop.ororo.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=4561291

отель краби резорт тайланд красивые пляжи на краби

Comprehensive uae consultants: feasibility studies, market analysis, strategy, optimization of costs and processes. We help you strengthen your position in Dubai, Abu Dhabi and other Emirates.

Нужен керосин? сколько стоит тонна авиационного керосина сертифицированное топливо по ГОСТ, поставки для аэропортов, авиапредприятий и вертолётных площадок. Помощь в подборе марки, оформление документов и быстрая доставка.

Нужен манипулятор? заказать манипулятор в москве организуем подачу спецтехники на стройку, склад или частный участок. Погрузка, разгрузка, перевозка тяжёлых и негабаритных грузов. Оперативный расчёт стоимости и выезд в день обращения.

Профессиональное маркетинг услуги агентства: аудит, позиционирование, digital-стратегия, запуск рекламных кампаний и аналитика. Поможем вывести бренд в онлайн, увеличить трафик и заявки из целевых каналов.

Профессиональная перевозка больных подъем на этаж, помощь при пересадке, фиксирующие носилки, заботливое отношение. Организуем транспортировку в больницы, реабилитационные центры и домой.

Нужна ботулинотерапия? ботулинотерапия препаратом диспорт помогаем смягчить мимику, освежить взгляд и предупредить появление новых морщин. Осмотр врача, противопоказания, грамотное введение и контроль результата на приёме.

Trading platform hypertrade crypto combines a user-friendly terminal, analytics, and portfolio management. Monitor quotes, open and close trades, and analyze market dynamics in a single service, available 24/7.

Нужен бетон? бетон м3 о выгодной цене с доставкой на объект. Свежий раствор, точное соблюдение пропорций, широкий выбор марок для фундамента, стяжек и монолитных работ. Быстрый расчет, оперативная подача миксера.

Use hyperevm dex to manage cryptocurrencies: a user-friendly dashboard, detailed statistics, and trade and balance tracking. Tools for careful risk management in a volatile market.

VIP эскорт в Москве, подробнее тут: заказать эскортницу москва Конфиденциальность и высокий уровень сервиса.

The best deepnude ai services for the USA. We’ll explore the pros and cons of each service, including speed, available effects, automation, and data privacy. Undress people in just a few clicks.

Growth acceleration occurs when you buy tiktok likes overcoming cold start challenges. New accounts benefit from engagement boosts helping bypass initial algorithmic skepticism toward unproven content.

Криптографически подписанные сообщения содержат официальная кракен ссылка с полным fingerprint PGP ключа операторов для независимой верификации через импорт публичного ключа в GPG.

Актуальная кракен ссылка сохраняется в закладках Tor браузера для быстрого доступа без необходимости повторного поиска адреса в источниках.

Новинний портал Ужгорода https://88000.com.ua головні події міста, політика, економіка, культура, спорт та життя городян. Оперативні новини, репортажі, інтерв’ю та аналітика. Все важливе про Ужгород в одному місці, зручно з телефону та комп’ютера.

A cozy swissotel resort Kolasin for mountain lovers. Ski slopes, trekking trails, and local cuisine are nearby. Rooms are equipped with amenities, Wi-Fi, parking, and friendly staff are available to help you plan your vacation.

Here’s the brutal truth: most HVAC failures take place because someone skipped a step. Did not calculate the load accurately. Used undersized equipment. Got wrong the insulation needs. We have fixed hundreds of these messes. And each and every time, we file away another insight. Like in 2017, when we began adding remote monitoring to all installation. Why? Because Sarah, our senior tech, got sick of watching homeowners lose money on poor temperature management. Now clients save $500+ yearly.

https://www.bbb.org/us/wa/marysville/profile/refrigeration/product-air-heating-cooling-and-electrical-1296-1000154140

Casino utan registrering https://casino-utan-registrering.se bygger pa en snabbare ide: du hoppar over kontoskapandet och gar direkt in via din bank-ID-verifiering. Systemet ordnar uppgifter och transaktioner i bakgrunden, sa anvandaren mots av en mer stromlinjeformad start. Det gor att hela upplevelsen far ett mer direkt, tekniskt och friktionsfritt upplagg utan extra formular.

I casino crypto https://crypto-casino-it.com sono piattaforme online che utilizzano valute digitali per transazioni rapide e sicure. Permettono di vedere in pratica i vantaggi della blockchain: trasparenza dei processi, assenza di intermediari, trasferimenti internazionali agevoli e un’interfaccia moderna, pensata per un’esperienza tecnologica degli utenti.

Casino utan svensk licens https://casinos-utan-licens.se ar onlineplattformar som drivs av operatorer med licens fran andra europeiska jurisdiktioner. De erbjuder ofta ett bredare utbud av tjanster och anvander egna regler for registrering och betalningar. For spelare innebar detta andra rutiner for sakerhet, verifiering och ansvarsfullt spelande.

Free Online Jigsaw Puzzle https://vps27160.prublogger.com/37828644/upgrade-your-focus-with-logic-based-puzzle-games play anytime, anywhere. Huge gallery of scenic photos, art and animals, customizable number of pieces, autosave and full-screen mode. No registration required – just open the site and start solving.

трансы новосибирск Тем не менее, сообщество транс-персон в Новосибирске растет и развивается, создавая онлайн-платформы и офлайн группы поддержки. Самоорганизация и взаимопомощь становятся ключевыми факторами в борьбе за свои права и за достойную жизнь. Поиск информации, обмен опытом и простое человеческое общение помогают преодолевать трудности и находить силы для дальнейшего пути. Новосибирск – это город возможностей, и даже в условиях сложностей, трансгендерные люди находят здесь свое место.

Explore hyper liquid and gain unlimited access to a modern, decentralized market. Trade derivatives, manage your portfolio, utilize analytics, and initiate trades in a next-generation ecosystem.

Choose multi hop routing hyperliquid as a convenient tool for trading and investing. The platform offers speed, reliability, advanced features, and fair pricing for cryptocurrency trading.

Use hyperliquid arbitrage finder for stable and efficient trading. The platform combines security, high liquidity, advanced solutions, and user-friendly functionality suitable for both beginners and professional traders.

Discover hyperliquid crypto a platform for fast and secure trading without intermediaries. Gain access to innovative tools, low fees, deep liquidity, and a transparent ecosystem for working with digital assets.

Choose hyperliquid dex list — a platform for traders who demand speed and control: over 100 pairs per transaction, flexible orders, HL token staking, and risk management tools. Support for algorithmic strategies and advanced analytics.

Check out hyperliquid trading, a modern DEX with its own L1: minimal fees, instant order execution, and on-chain transparency. Ideal for those who want the speed of a CEX and the benefits of decentralization.

Inbet Nigeria — thousands of live sports events blackjack Inbet Nigeria . Fast payouts, high odds, 24/7 support, and match broadcasts. Bet on sports and play slots, roulette, blackjack at Inbet Nigeria. Mobile app, jackpots, promos, welcome & deposit bonuses.

Открываешь бизнес? whitesquarepartners открытие бизнеса в оаэ полный пакет услуг: консультация по структуре, подготовка и подача документов, получение коммерческой лицензии, оформление рабочих виз, помощь в открытии корпоративного счета, налоговое планирование и пострегистрационная поддержка. Гарантия конфиденциальности.

Хотите открыть компанию оаэ? Предоставим полный комплекс услуг: выбор free zone, регистрация компании, лицензирование, визовая поддержка, банковский счет и бухгалтерия. Прозрачные условия, быстрые сроки и сопровождение до полного запуска бизнеса.

Предлагаем создание холдингов оаэ для международного бизнеса: подбор free zone или mainland, разработка структуры владения, подготовка учредительных документов, лицензирование, банковское сопровождение и поддержка по налогам. Конфиденциальность и прозрачные условия работы.

Хочешь фонд? личные фонды оаэ — безопасный инструмент для защиты активов и наследственного планирования. Помогаем выбрать структуру, подготовить документы, зарегистрировать фонд, обеспечить конфиденциальность, управление и соответствие международным требованиям.

Профессиональное учреждение семейных офисов оаэ: от разработки стратегии управления семейным капиталом и выбора юрисдикции до регистрации, комплаенса, настройки банковских отношений и сопровождения инвестиционных проектов. Полная конфиденциальность и защита интересов семьи.

Хотите открыть счёт? открыть счет в банке оаэ Подбираем оптимальный банк, собираем документы, готовим к комплаенсу, сопровождаем весь процесс до успешного открытия. Поддерживаем предпринимателей, инвесторов и резидентов с учётом всех требований.

Playbet Kenya offers – playbet app Kenya betting on dozens of sports in live and pre-match (line) modes, a live online casino with tables available 24/7, and a huge selection of popular slots. A unique welcome bonus is offered for deposits made in cryptocurrency. Round-the-clock support and fast withdrawals of winnings.

Нужна виза инвестора в оаэ? Подберём оптимальный вариант — через бизнес, долю в компании или недвижимость. Готовим документы, сопровождаем на всех этапах, обеспечиваем корректное прохождение комплаенса и получение резидентского статуса.

Профессиональное налоговое консультирование оаэ: разбираем вашу ситуацию, подбираем оптимальную корпоративную и личную структуру, помогаем учесть требования местного законодательства, корпоративного налога и substance. Сопровождаем бизнес и инвестиции на постоянной основе.

Комплексные бухгалтерский учет в оаэ: финансовая отчётность, налоговые декларации, управление первичными документами, аудит, VAT и corporate tax. Обеспечиваем точность, своевременность и полное соответствие законодательству для стабильной работы вашего бизнеса.

Оформление золотая виза оаэ под ключ: анализ вашей ситуации, подбор оптимальной категории (инвестор, бизнес, квалифицированный специалист), подготовка документов, сопровождение подачи и продления статуса. Удобный формат взаимодействия и конфиденциальный сервис.

Профессиональная легализация документов в оаэ: нотариальное заверение, Минюст, МИД, консульства, сертифицированные переводы. Сопровождаем весь процесс от проверки документов до финального подтверждения. Подходит для компаний, инвесторов и частных клиентов.

Профессиональное консульское сопровождение оаэ для частных лиц и бизнеса: консультации по визовым и миграционным вопросам, подготовка обращений, запись в консульство, помощь при подаче документов и получении решений. Минимизируем риски отказов и задержек.

Помогаем открыть брокерский счет в оаэ: подбор надёжного брокера, подготовка документов, прохождение KYC, сопровождение подачи и активации. Подходит для частных инвесторов, семейных офисов и компаний. Доступ к мировым рынкам и комфортные условия работы с капиталом.

Предлагаем корпоративные услуги в оаэ для действующих и новых компаний: регистрация и перерегистрация, выпуск и передача долей, протоколы собраний, обновление лицензий, KYC и комплаенс. Обеспечиваем порядок в документах и соответствие требованиям регуляторов.

рассвет краби санда резорт краби

Playbet Nigeria offers betting – Racing & Numbers Online Nigeria on dozens of sports in live and pre-match (line) modes, a live online casino with tables available 24/7, and a huge selection of popular slots. A unique welcome bonus is offered for deposits made in cryptocurrency. Round-the-clock support and fast withdrawals of winnings.

Разрабатываем опционные планы в оаэ под ключ: анализ корпоративной структуры, выбор модели vesting, подготовка опционных соглашений, настройка механики выхода и выкупа долей. Помогаем выстроить прозрачную и понятную систему долгосрочной мотивации команды.

Corporate corporate bank account opening in dubai made simple: we help choose the right bank, prepare documents, meet compliance requirements, arrange interviews and support the entire onboarding process. Reliable assistance for startups, SMEs, holding companies and international businesses.

Get your golden visa uae with full support: we analyse your profile, select the right category (investor, business owner, specialist), prepare a compliant file, submit the application and follow up with authorities. Transparent process, clear requirements and reliable guidance.

Нужна поддержка по трудовым вопросам оаэ? Консультируем по трудовым договорам, рабочим визам, оформлению сотрудников, переработкам, отпускам и увольнениям. Готовим рекомендации, помогаем минимизировать риски штрафов и конфликтов между работодателем и работником.

Разработка соглашения об управлении оаэ: фиксируем правила принятия решений, распределение ролей, отчётность и контроль результатов. Учитываем особенности вашей компании, отрасли и требований регуляторов. Помогаем выстроить устойчивую систему корпоративного управления.

Professional business setup in dubai: advisory on jurisdiction and licence type, company registration, visa processing, corporate bank account opening and ongoing compliance. Transparent costs, clear timelines and tailored solutions for your project.

Comprehensive consular support uae: embassy and consulate liaison, legalisation and attestation of documents, visa assistance, translations and filings with local authorities. Reliable, confidential service for expatriates, investors and corporate clients.

Comprehensive tax consultant uae: advisory on corporate tax, VAT, group restructuring, profit allocation, substance and reporting obligations. We provide practical strategies to optimise taxation and ensure accurate, compliant financial management.

Trusted accounting services dubai providing bookkeeping, financial reporting, VAT filing, corporate tax compliance, audits and payroll services. We support free zone and mainland companies with accurate records, transparent processes and full regulatory compliance.

Want to obtain an investor visa uae? We guide you through business setup or property investment requirements, prepare documentation, submit your application and ensure smooth processing. Transparent, efficient and tailored to your goals.

Launch your fund setup uae with end-to-end support: structuring, legal documentation, licensing, AML/KYC compliance, corporate setup and administration. We help create flexible investment vehicles for global investors and family wealth platforms.

End-to-end corporate setup uae: company formation, trade licence, corporate documentation, visa processing, bank account assistance and compliance checks. We streamline incorporation and help establish a strong operational foundation in the UAE.

Need legalization of documents for uae? We manage the entire process — review, notarisation, ministry approvals, embassy attestation and translation. Suitable for business setup, visas, employment, education and property transactions. Efficient and hassle-free.

Comprehensive family office setup uae: from choosing the right jurisdiction and legal structure to incorporation, banking, policies, reporting and ongoing administration. Tailored solutions for families consolidating wealth, protecting assets and planning succession.

Set up a uae holding company with full legal and corporate support. We help select the right jurisdiction, prepare documents, register the entity, coordinate banking and ensure compliance with substance, tax and reporting rules for international groups.

https://bravomos.ru/ bravomos

Проект загородного дома Проект загородного дома требует тщательного продумывания архитектурных решений и планировки. На начальном этапе важно определиться с размерами участка и его особенностями. Далее, стоит разработать схему, учитывающую оптимальное использование природных ландшафтов. Каждый элемент – от расположения комнат до окон – должен быть спроектирован так, чтобы дом был не только красивым, но и удобным для проживания. Энергоэффективные технологии, такие как солнечные панели и утепленные стены, помогут снизить затраты на отопление и электричество, что особенно актуально в современных условиях.

Need a power of attorney uae? We draft POA documents, organise notary appointments, handle MOFA attestation, embassy legalisation and certified translations. Ideal for delegating authority for banking, business, real estate and legal procedures.

Need a will in uae? We help structure inheritances, appoint executors and guardians, cover local and foreign assets and prepare documents in line with UAE requirements. Step-by-step guidance from first consultation to registration and safe storage of your will.

Open a brokerage account uae with full support. We review your goals, recommend regulated platforms, guide you through compliance, handle documentation and assist with activation. Ideal for stock, ETF, bond and multi-asset trading from a trusted jurisdiction.

Complete uae work visa support: from eligibility check and document preparation to work permit approval, medical tests and residence visa issuance. Ideal for professionals moving to Dubai, Abu Dhabi and other emirates for long-term employment.

Авиабилеты в Китай https://chinaavia.com по выгодным ценам: удобный поиск рейсов, сравнение тарифов, прямые и стыковочные перелёты, актуальные расписания. Бронируйте билеты в Пекин, Шанхай, Гуанчжоу и другие города онлайн. Надёжная оплата и мгновенная выдача электронного билета.

Market cycle awareness crypto Binance trading signals, beyond the hype and the promises of instant riches, represent the democratization of sophisticated market analysis. These signals, whether meticulously crafted by seasoned analysts or spat out by the cold, calculating logic of AI, offer a scaffolding of insights. They attempt to distill the chaos of market sentiment into actionable intelligence – entry exit levels sharp enough to draw blood, stop-loss recommendations acting as digital lifelines, and take-profit targets crypto calibrated to maximize gain while mitigating risk. The siren song of Binance VIP signals, echoing through premium crypto signal telegram channels, underscores the premium placed on precise, actionable information delivered with the urgency of a ticking clock.

This is the ugly truth: the majority of septic companies just maintain tanks. They act like quick-fix salesmen at a disaster convention. But Septic Solutions? They are special. It all originated back in the beginning of the 2000s when Art and his brothers—just kids hardly tall enough to lift a shovel—helped install their family’s septic system alongside a experienced pro. Visualize this: three youngsters knee-deep in Pennsylvania clay, understanding how soil absorption affects drainage while their peers played Xbox. “We did not just dig ditches,” Art shared with me last winter, hot coffee cup in hand. “We learned how ground whispers mysteries. A patch of cattails here? That’s Mother Nature screaming ‘high water table.'”

https://www.mapquest.com/us/washington/septic-solutions-llc-778353593

The ultimate sci-fi buddy comedy is waiting for you. The Project Hail Mary PDF is the best way to read it. This digital file is compatible with all major devices. Enjoy the banter and the bravery of the two heroes. https://projecthailmarypdf.top/ when does project hail mary movie come out

High-quality service site shop invites webmasters to the vast catalog of social accounts. The core value of our shop is our exclusive wiki section, where you can find secret strategies on ad campaigns. Inside the materials, experts share insights on using trackers to increase efficiency for your daily work. The shop offers profiles of FB, Insta, Telegram for all needs: ranging from softregs up to verified business managers with cookies.

Descubre casino cocoa: tragamonedas clasicas y de video, juegos de mesa, video poker y jackpots en una interfaz intuitiva. Bonos de bienvenida, ofertas de recarga y recompensas de fidelidad, ademas de depositos y retiros rapidos y un atento servicio de atencion al cliente. Solo para adultos. Mayores de 18 anos.

знакомства рядом серьезные знакомства красивые девушки и парни это не фантастика, миллионы анкет реально помогает в поиске.

Platforma internetowa mostbet: zaklady przedmeczowe i na zywo, wysokie kursy, akumulatory, zaklady na sumy i handicapy, a takze popularne sloty i kasyno na zywo. Bonus powitalny, regularne promocje, szybkie wyplaty na karty i portfele.

продать или сдать в аренду аккаунт бк Аренда аккаунтов букмекерских контор представляет собой альтернативный вариант, когда лицо, владеющее аккаунтом, предоставляет его во временное пользование за определенную плату. Этот путь также не лишен рисков, поскольку владелец аккаунта не может полностью контролировать действия арендатора, что может привести к нарушению правил букмекерской конторы и, как следствие, к негативным последствиям для обеих сторон.

Prodej reziva https://www.kup-drevo.cz v Ceske republice: siroky vyber reziva, stavebniho a dokoncovaciho reziva, tramu, prken a stepky. Dodavame soukromym klientum i firmam stalou kvalitu, konkurenceschopne ceny a dodavky po cele Ceske republice.

Professional backup storage secure, efficient, fast and privacy-focused reliable FTP Backup storage in Europe. 100% Dropbox European alternative. Protection on storage account. Choose European Backup Storage for peace of mind, security, and reliable 24x7x365 data management service.

Вызов электрика https://vash-elektrik24.ru на дом в Москве: оперативный выезд, поиск и устранение неисправностей, установка розеток и выключателей, подключение техники, ремонт проводки. Квалифицированные мастера, точные цены, гарантия на работы и удобное время приезда.

Хочешь сдать авто? https://vykup-auto78.ru/ быстро и безопасно: моментальная оценка, выезд специалиста, оформление сделки и мгновенная выплата наличными или на карту. Покупаем автомобили всех марок и годов, включая битые и после ДТП. Работаем без скрытых комиссий.

University https://vsu.by offers modern educational programs, a strong faculty, and an active student life. Practice-oriented training, research projects, and international collaborations help students build successful careers.

WhatsApp Business ООО Торгово-транспортное предприятие “Острое Жало”

работа онлайн вк Говоря о находках Озон, мы открываем для себя еще одну вселенную возможностей. Находки Озон одежда – это альтернативный взгляд на моду, предлагающий свои уникальные коллекции и дизайнерские решения. Интересные находки на Озон часто становятся приятным сюрпризом, открывая новые бренды и товары, о которых мы раньше не знали. Мужские находки Озон также заслуживают внимания, предлагая широкий выбор стильной и качественной одежды и аксессуаров. В конечном итоге, выбор между находками Вайлдберриз Озон – это вопрос индивидуальных предпочтений и привычек.

Cryptocasino reviews https://crypto-casinos-canada.com in Canada – If you’re looking for fast BTC/ETH transactions and clear terms, cryptocasino reviews will help you evaluate which platforms offer transparent bonuses and consistent payouts.

BankID-fria kasinon https://casinos-utan-bankid.com Manga spelare forbiser hur mycket uttagsgranser och verifieringskrav varierar, men BankID-fria kasinon hjalper dig att jamfora bonusar, betalningsmetoder och tillforlitlighet.

Casinos, die Paysafecard https://paysefcard-casino-de.info akzeptieren: Viele Spieler in Deutschland mochten ihr Konto aufladen, ohne ihre Bankdaten anzugeben. Casinos, die Paysafecard akzeptieren, ermoglichen sichere Prepaid-Einzahlungen mit einem festen Guthaben. So behalten Sie die volle Kontrolle uber Ihre Ausgaben und konnen weiterhin Spielautomaten und Live-Dealer-Spiele spielen.

Проблемы с алкоголем? вывод из запоя врач на дом: анонимная помощь, круглосуточный выезд врача, детоксикация, капельницы, стабилизация состояния и поддержка. Индивидуальный подход, современные методы и контроль здоровья. Конфиденциально и безопасно.